Elvish Yadav faces NDPS and Wildlife charges in Noida. Bail granted amid questions on FIR validity, informant eligibility, and lack of recovery evidence.

A case involving YouTuber Elvish Yadav raises key procedural and legal concerns under the Wildlife Protection and NDPS Acts.

Legal Background: FIR, Charges, and Cognisance

The ongoing criminal case involving YouTuber and social media influencer Elvish Yadav @ Siddharth originates from an FIR lodged at Police Station Sector-49, Noida, Gautam Buddha Nagar district, Uttar Pradesh. The complaint resulted in a complex chargesheet citing multiple legal provisions from the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860, and Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 (NDPS Act).

The First Additional Chief Judicial Magistrate (ACJM), Gautam Buddha Nagar, has taken cognisance of the offences and issued a summoning order against Yadav. As per the chargesheet, the sections invoked include:

- Wildlife Protection Act: Sections 9, 39, 48A, 49, 50, and 51

- IPC: Sections 284 (negligent conduct with poisonous substance), 289 (negligent conduct with respect to animals), and 120B (criminal conspiracy)

- NDPS Act: Sections 8, 22, 29, 30, and 32

Defence Arguments: Competence of Informant and Lack of Recovery

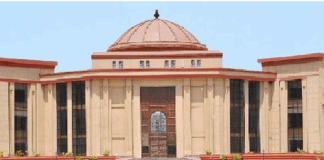

Appearing before the Allahabad High Court, Senior Advocate Navin Sinha raised serious legal objections regarding the maintainability of the FIR. The core submission was that the informant lacked locus standi under the Wildlife Protection Act, claiming the individual had previously served as an Animal Welfare Officer but was no longer holding that position at the time the FIR was registered.

The argument, therefore, revolves around the competency of the informant — a fundamental procedural aspect that could render the entire investigation void ab initio if found lacking.

In addition, the defence strongly asserted that:

- No snakes or other prohibited wildlife were recovered from Yadav.

- No narcotic substances or psychotropic drugs were found in his possession.

- Yadav was allegedly not present at the party where the offences are said to have occurred.

These factual assertions challenge the substantive evidence base of the prosecution, suggesting an absence of incriminating material, at least directly implicating the accused.

Bail Status and Legal Developments

Elvish Yadav had earlier been granted bail, and currently remains out of custody while court proceedings continue. The grant of bail indicates a prima facie assessment by the lower court that custodial interrogation was not required at the time.

The case has since drawn significant public and media attention, owing both to Yadav’s celebrity status and the gravity of statutory offences involved, particularly those under the NDPS Act, which are non-bailable and involve strict liability and reverse burden of proof.

Legal Provisions in Question: Brief Explainers

- Wildlife Protection Act: Section 9 prohibits hunting of wild animals, while Section 39 prescribes ownership and possession limitations. Sections 48A and 49 govern transport and trade in wildlife, and Section 51 provides for penalties.

- NDPS Act: Section 8 restricts operations involving narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances; Section 22 deals with punishment for possession; Sections 29–32 cover abetment, criminal conspiracy, and attempt to commit offences under the Act.

- IPC Provisions: Sections 284 and 289 concern negligent conduct, while Section 120B captures conspiracy.

For law students, this case provides a valuable opportunity to study the overlap between environmental law and narcotics law, as well as the procedural prerequisites for filing complaints under special statutes.

Public Impact and Relevance

Despite the absence of direct recovery, the case highlights broader concerns:

- Celebrity accountability under criminal law

- Procedural integrity of FIRs under special legislation

- The role of former public officers acting as complainants

While the case continues, its implications on interpretation of statutory competence, evidentiary thresholds, and judicial discretion in granting bail will likely contribute to future legal discourse.