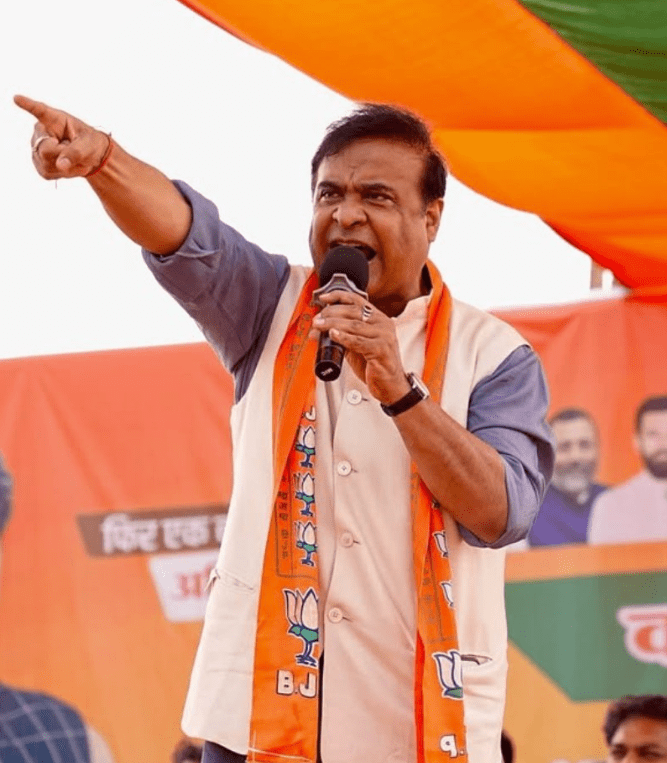

The refusal of the Supreme Court of India to entertain petitions seeking criminal action against Himanta Biswa Sarma brings into focus a deeper constitutional issue: how Indian law defines, regulates, and adjudicates hate speech.

This analysis examines the constitutional framework, statutory provisions, key precedents, and how they apply to the present controversy.

I. Constitutional Framework: Free Speech vs. Public Order

1. Article 19(1)(a): Freedom of Speech

The Constitution guarantees freedom of speech and expression.

2. Article 19(2): Reasonable Restrictions

This freedom is subject to restrictions in the interests of:

- Public order

- Decency or morality

- Incitement to an offence

- Sovereignty and integrity of India

Hate speech cases usually fall under:

- Public order

- Incitement to an offence

The core legal question in such cases is:

Does the speech merely express a political opinion, or does it cross into incitement or promotion of hatred that threatens public order?

II. Statutory Framework: Criminal Law Provisions

India does not have a single consolidated “Hate Speech Act.” Instead, it relies on provisions in the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (earlier Indian Penal Code).

Commonly invoked provisions include:

- Section 153A: Promoting enmity between groups on grounds of religion, race, language, etc.

- Section 295A: Deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings.

- Section 505(2): Statements creating or promoting enmity, hatred or ill-will between classes.

To secure conviction, prosecution must establish:

- Mens rea (intention)

- Speech targeting an identifiable group

- Likely or actual disturbance of public order

III. Judicial Tests Developed by the Supreme Court

1. Proximity Test (Public Order Doctrine)

In Ram Manohar Lohia v State of Bihar, the Court held:

There must be a proximate and direct nexus between the speech and disturbance of public order.

Mere offensive or unpopular speech is not enough.

2. Tendency to Incite Violence

In Pravasi Bhalai Sangathan v Union of India, the Court acknowledged the menace of hate speech but declined to frame new guidelines, stating that existing laws were sufficient.

The Court emphasized:

- Only speech with a tendency to incite violence or public disorder can be criminalized.

- Political speech enjoys high protection.

3. Incitement Standard

In Shreya Singhal v Union of India, while striking down Section 66A of the IT Act, the Court drew a distinction between:

- Advocacy

- Discussion

- Incitement

Only incitement can be restricted.

This judgment significantly raised the threshold for criminalizing speech.

4. Hate Speech and Electoral Context

In Abhiram Singh v C D Commachen, the Court interpreted electoral law to prohibit appeals to religion during elections.

Though not directly about criminal hate speech, it reinforced:

- Secularism as a constitutional value

- Limits on communal mobilization during elections

IV. Application to the Present Controversy

The allegations against Himanta Biswa Sarma involve:

- A video showing symbolic shooting at a target allegedly depicting Muslims.

- Statements about “Miyas” (Bengali-speaking Muslims), allegedly portraying them as “illegal infiltrators.”

Legal Questions That Would Arise in Court

If the case proceeds before the Gauhati High Court, the court would examine:

1. Was There Targeting of a Protected Group?

Muslims are a religious community — clearly a protected class under Section 153A-type provisions.

2. Was There Intent?

Courts require proof of deliberate intent to promote enmity.

Political rhetoric, even if harsh, must show malicious intention, not mere criticism or policy positioning.

3. Was There Likelihood of Public Disorder?

Was the speech likely to:

- Trigger violence?

- Create communal tension?

- Disrupt public peace?

Without a proximate connection to disorder, prosecution becomes difficult.

4. Context Matters

The Court often evaluates:

- Tone

- Audience

- Platform (political rally vs private setting)

- Timing (election season)

Political speech receives broader latitude.

V. Judicial Restraint and Institutional Concerns

The Supreme Court’s refusal to entertain the plea directly is also jurisprudentially significant.

It reflects:

1. Respect for Judicial Hierarchy

High Courts under Article 226 are empowered to:

- Direct registration of FIRs

- Order SITs

- Monitor investigations

2. Avoidance of Politicization

The bench’s observation about a “trend before elections” signals concern about:

- Courts being used as pre-election battlegrounds

- Judicial process becoming part of campaign strategy

This reflects the doctrine of constitutional self-restraint.

VI. Broader Doctrinal Tensions in Indian Hate Speech Law

Indian jurisprudence reveals an unresolved tension between:

| Liberal Free Speech Model | Communitarian Public Order Model |

|---|---|

| Protect even offensive speech | Restrict speech that harms social harmony |

| Focus on incitement to violence | Focus on group dignity & communal peace |

India leans toward the public order model, but post-Shreya Singhal, courts demand a high threshold of incitement.

VII. Structural Problems in Hate Speech Prosecution

- Selective Enforcement — Often politically influenced.

- Overbreadth — Risk of suppressing legitimate political dissent.

- Chilling Effect — Criminal law may deter democratic debate.

- Ambiguity in Terms — What constitutes “enmity” or “hatred”?

VIII. Key Takeaway: The High Legal Threshold

For criminal liability in hate speech cases involving political leaders, courts typically require:

- Clear identification of a protected group

- Demonstrable malicious intent

- Direct or imminent risk to public order

Symbolic acts and political rhetoric may be condemned ethically or politically, but criminal conviction demands strict proof.

Conclusion

The refusal of the Supreme Court of India to intervene at the threshold stage does not settle the question of hate speech. It merely reinforces procedural discipline.

If pursued before the Gauhati High Court, the case would test the evolving contours of Indian hate speech jurisprudence — especially the delicate balance between:

- Democratic political speech

- Protection of minority communities

- Preservation of public order

- Constitutional morality

In essence, Indian hate speech law remains a battlefield between liberty and equality — and courts continue to define its boundaries case by case.

Himanta Biswa Sarma